“It feels like a big injustice,” says 40-year-old Helen Bone as she sips tea in her kitchen in Middlesbrough, in England’s northeast.

In 2021, Helen was diagnosed with mesothelioma – an incurable cancer the United Kingdom’s National Health Service (NHS) says is overwhelmingly linked to exposure to asbestos, a carcinogenic mineral that has been part of the infrastructure of her life since childhood.

“These are the cards I’ve been dealt … to be diagnosed with something that was brought into our country and then manufactured into our buildings,” she reflects.

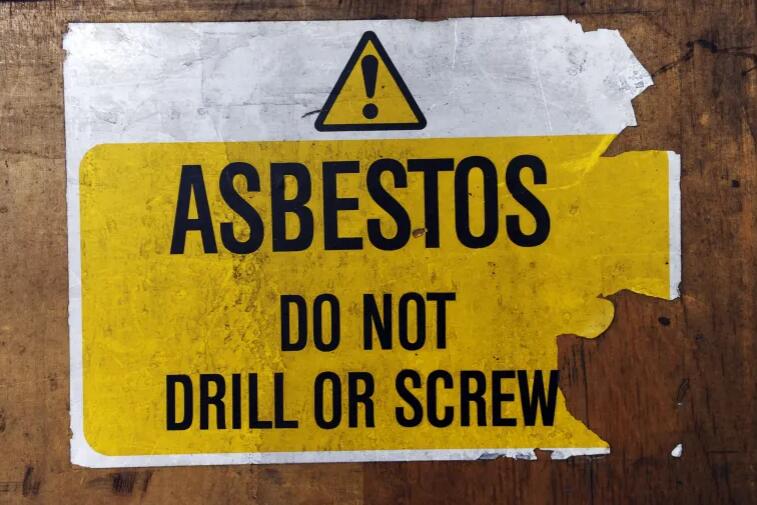

Although the UK has no asbestos mines, for about 150 years, the mineral was imported, mostly from Canada, and used extensively in construction. The naturally occurring mineral is made up of heat-resistant fibres and there are three main types commonly found in the UK – brown, white and blue. Between the 1930s and the 1980s, it was mixed into cement, roofing felt, texture walls, ceiling coverings and floor tiles, and used on roofs, gutters and window seals and to lag or insulate boilers and pipes. Brown asbestos – which the overwhelming majority of mesothelioma cases are believed to be linked to – was banned in 1985; a ban on other types of asbestos followed in 1999. But older buildings still contain the hazardous material and there is no clear plan in place to remove it.

As part of a wider investigation across nine European countries, Al Jazeera investigated the continuing threat posed by asbestos in the UK, where, every year, more than 5,000 people die from asbestos-related cancers. More than half of those deaths are from mesothelioma, which is a cancer of the lining of the lungs or abdomen. In England, fewer than half of patients live for a year or more after diagnosis, and just over five in 100 survive their mesothelioma for five years or more, according to the charity Cancer Research UK.

The UK has the highest rate of mesothelioma deaths per capita in the world, according to the Health and Safety Executive (HSE), Britain’s national regulator for workplace health and safety.

But the dangers have long been known.

The first article that laid out the health hazards of asbestos-related dust appeared in the British Medical Journal nearly a century ago. Then, in the 1960s, mesothelioma was recognised as being linked to exposure to asbestos. A number of other cancers have been linked to asbestos exposure, including asbestosis, lung cancer, ovarian cancer and cancer of the larynx.

Asbestos is now estimated to kill more than 200,000 people a year globally, according to Dr Jukka Takala, the former president of the International Commission on Occupational Health and the co-author of a 2018 scientific paper, Global Asbestos Disaster, which suggests the figure may be as high as 255,000 a year.

“As soon as people did understand [the dangers of asbestos], there should have been change,” says Helen, a mother of three daughters who, until last year, worked as an advanced critical care practitioner nurse for the NHS. She made the difficult decision to take ill-health retirement last August. “I love my job … I will miss it so much,” she says, before pointing out the small clinic her husband, Mark, built in their back garden so that she can work as an aesthetic nurse practitioner, offering cosmetic treatments like Botox. “I’m not the type of person who can sit around,” she explains.

She has also been writing what she calls her “cancer log“, a blog called It Is What It Is, where she chronicles her journey, including the gruelling chemotherapy she must undergo to hopefully prolong her life, even though it cannot cure her.

‘Waiting for an accident to happen’

According to the HSE, most of those exposed to asbestos inhale loose fibres that become airborne when materials that contain it are damaged or disturbed – through building work, natural damage or weathering over time.

Asbestos is “the UK’s number one occupational killer”, according to Charles Pickles, an asbestos campaigner who has spent years highlighting the dangers and the need for policy change to tackle them.

Current UK regulations stipulate that asbestos only needs to be removed if it is damaged.

Large-scale removal comes with risks, including fibres and dust particles being disturbed. While regulations stipulate that asbestos must be removed by contractors with a special licence, there is, for example, a danger that when it is loaded into skips that travel along residential roads to special landfill sites, every jolt can release deadly fibres into the air.

However, activists argue that waiting for asbestos-containing materials to deteriorate before removing them is not sustainable and that more proactive action needs to be taken.

“We are waiting for an accident to happen before we intervene. That’s the wrong way round,” says Charles.

He argues that “if you’re worried about the standards of asbestos removal, then you ought to increase your standards”.

The HSE said in a statement to Al Jazeera: “Concern about asbestos is understandable and we sympathise with those who have been exposed and suffer from its devastating impact. Risk of exposure is low as long as the regulations are followed. We provide clear, free guidance to those with responsibility for managing asbestos and we will continue to hold to account those who fail to protect people properly.”

No longer an ‘old man’s disease’

Previously, men working in building-related activities, as well as other heavy industries such as shipbuilding, were the most likely victims of asbestos-related diseases. But data suggests the number of women dying as a result of exposure is growing, with Cancer Research UK finding that 17 percent of mesothelioma cases are now in women. In 2020, 2,544 people died from mesothelioma – a rise of six percent from the previous year. Of those, 459 were women.

Cancer Research UK found that the rate of new mesothelioma cases in women has doubled since the early 1990s, while increasing by around half in men. A study by Mesothelioma UK, with the University of Sheffield, found that high-risk occupations for women differ from those for men, with female teachers, healthcare workers and clerical workers all facing increased risk.

“I was guilty of the thinking that this was an old man’s disease,” Helen says. “But the more you go on the support groups, the more you notice how many women have it now.”

Asbestos exposure usually has a latency period of some decades. Given Helen’s age, she knows that she was either exposed as a nurse, as a patient, or at school. As a child, she had a cleft palate, so was in and out of hospital. “My first operation was at six weeks old; I had 13 operations altogether whilst I was a child. I was surrounded by people doing an amazing job and I thought, I could do that, and because I’ve been a patient, I really understood what it was like on the other side.”

The hospital she was treated in was made from asbestos-containing materials, as was the school she attended and the hospital she worked in.

“At work, I was always the one fixing the tiles, or drilling a hole in the wall, so it doesn’t surprise me that I got the diagnosis,” she says.

But because it takes a long time for asbestos-related diseases to develop, once a patient is diagnosed it is usually too late and treatment options are limited. Helen is part of an experimental multi-drug clinical trial, but beyond that, the only choices mesothelioma patients have are aggressive surgery, chemo and radiotherapy – as well as palliative care to make life more comfortable. None of these cures the cancer.

No warning of the dangers

Ron Snaith is a 67-year-old former shipyard worker in Newcastle upon Tyne who was diagnosed with mesothelioma in 2018. He decided to have aggressive surgery to help prolong his life.

The northeast of England, where both Helen and Ron live, has one of the highest rates of asbestos-related cancer in the UK, linked to the region’s industrial past and, in particular, the shipping industry and a defunct insulation factory in the area, where asbestos was used.

Walking around the former shipyard with Ron and Sarah Thomas, the senior benefits officer for Mesothelioma UK, a charity that supports anyone affected by mesothelioma, his friend Bob Hepburn jokes that Ron is tough because “he’s a Jarrow man”. Ron points out the town of Jarrow, on the south bank of the River Tyne, explaining how he and thousands of other workers would cycle and walk through a tunnel, just under 900 feet (274 metres) long, that ran under the river to clock on.

Later, over coffee, the two men remember that time with affection, bringing out albums of photos and clippings that chronicle their working lives. But Ron says, “A lot of the lads died around 40 years of age. We’ve stood the test of time and been lucky. Until recently.”

Ron’s surgery removed all visible signs of the tumour and the affected lung lining. “I was what they called an ideal candidate,” he explains with humour. “I went to Bart’s Hospital and they put a shark bite in me, and pulled the ribs apart and cut the tumour out. And then they took out my diaphragm and scraped all the cancer out, on my heart and all down my spine.”

Ron’s recovery was slow. “I was like a skeleton. The lads came and pushed me around, and over the space of a month, I gave my wheelchair back. I have built myself up and Bob and me have continued to do the Great North Run.” It was difficult surgery that took a toll on Ron, but it has helped prolong his life and, he stresses, “I would have it again.”

Looking at the photos of men larking about and of ships launching, Sarah holds up an historical map of the area, the Tyne running through it and the shipyards and factories clustered around it. “There’s a big connection with asbestos here. There were thousands of lads coming here to work every day. The first thing I do when I meet someone who has been diagnosed is do a work history. In the three years of doing this job, you hear the same names [of shipyards and factories] again and again. This is where we come from,” she says.

“We were given paper suits over our boiler suits when we worked with asbestos,” Ron chips in. “I used to volunteer for everything, I had a young family to support, and we got an extra allowance for it.”

The two men say they regret nothing about working together in the yards. Except that they feel they could have been better warned about the dangers of asbestos.

Britain’s asbestos legacy

The HSE estimates that between 210,000 and 400,000 buildings in the UK contain asbestos. Other sources say there are about six million tonnes of asbestos, spread across approximately 1.5 million buildings – the most asbestos per capita in Europe. Between 1920 and 2000, Europe accounted for more than 50 percent of all asbestos traded throughout the world, with the UK importing more asbestos per capita than any other country.

In looking into the state of asbestos in buildings in the UK, Al Jazeera used a combination of Freedom of Information Requests (FOI), Environmental Information Regulation requests and expert interviews, finding that asbestos was highly prevalent in buildings which are routinely surveyed.

FOI requests to the Department for Education found that nearly 81 percent of schools – about 34,000 – reported that asbestos was present in their buildings. Information requests to the NHS established that more than 90 percent, or 1,229, of freehold, or wholly owned, hospital buildings contained asbestos. Of those buildings, this investigation found that 29 percent of asbestos-containing materials in hospital buildings were deemed to be damaged.

The HSE, which is responsible for monitoring and enforcing the safety of asbestos in buildings across the UK, had its funding cut by 46 percent between 2010/11 and 2019/20, due to government austerity policies. Asbestos enforcement activity has been reduced, although the HSE has said it intends to increase inspections going forward.

In the buildings surveyed by asbestos consultants, between 29 percent and 70 percent of asbestos was judged to be damaged. The range varies greatly depending on the source, with the NHS on the lower end and the asbestos consulting industry on the higher end.

The UK ‘in denial’

Asbestos was banned across the European Union in 2005, yet millions of tonnes remain in buildings across Europe.

In Europe, only the Flanders region of Belgium and Poland have developed strategies to remove asbestos. Poland is the only EU member state with a national action plan to eradicate it by 2032.

But despite this, the UK still fares badly when compared with the rest of Europe.

Liz Darlison, the CEO of the charity Mesothelioma UK and a consultant nurse specialising in mesothelioma, told Al Jazeera: “We have such poor guidelines compared to our European neighbours, who have been far more proactive on prevention. The government has been non-committal on a timetable [for removal].”

This means, she adds, that people “continue to be diagnosed with a rare and avoidable cancer, for which there is hardly any treatment”.

In 2021, the Work and Pensions Select Committee called for evidence about the HSE’s approach to asbestos management. Select committees work in both houses of Parliament to check and report on government policies and include parliamentary members from all political parties.

The committee heard evidence from researchers and public health officials from the Netherlands, France and Germany suggesting that the UK’s approach is significantly less stringent and effective than its neighbours.

Compared with other European countries the UK’s approach to measuring airborne asbestos fibres is also less sensitive and less precise, and UK occupational exposure limits are significantly higher – as much as 50 times greater than those in the Netherlands, for example.

“People overseeing the control of asbestos seemed to be in denial about the number and level of exposures,” says Charles Pickles. He gave evidence to the parliamentary select committee last year, arguing for more urgency in removing asbestos.

After six months of deliberation, the select committee unanimously recommended that the government set a 40-year deadline to remove asbestos from public and commercial buildings, arguing that the risk to health is only likely to increase as building renovations take place as part of the UK’s efforts to move towards net zero emissions.

The select committee’s chair, Sir Stephen Timms MP, told Al Jazeera: “It is striking for me that asbestos remains the biggest workplace cause of fatalities, 20 years after it was banned – and it is a worrying feature that a growing number of people from the health and education sectors … are dying from asbestos-related diseases.”

The government responded to the select committee, saying there was no “compelling evidence” to justify active removal and that there was no need for a register.

Charles told Al Jazeera: “Asbestos is in 60 percent of homes and high street shops, 80 percent of schools and hospitals. Normal members of the public don’t know where asbestos is in the buildings we visit.

“We need to prioritise the removal of high-risk materials which could affect high-risk groups – so schools first, then social housing and hospitals, accommodation and office blocks.”

John Richards, the spokesperson for Asbestos Testing and Consultancy (ATaC) which works closely together with the National Organisation of Asbestos Consultants (NORAC) – organisations representing asbestos surveyors and analysts – told Al Jazeera, in a statement: “Our collective memberships has provided data on almost 750,000 asbestos items that were inspected between October 2021 and March 2022 and based on criteria determined by HSE almost 70 percent of these items [or asbestos-containing materials] were damaged.”

Because data collection by and for the government is so poor, the HSE conceded in a recent report that it has no idea of how many deaths might occur beyond 2030, acknowledging that though the government expects deaths to peak between 2014-2035 due to the earlier ban on asbestos, this is not certain.

Frustrated by the lack of government action, some asbestos consultants have grouped together to create a digital asbestos register, with which any workers entering a building can scan a QR code to see exactly where asbestos is present. Andy Brown, one of the co-founders of the register, which is currently trialling the technology, said: “Governments are not good at looking forward and don’t like to deliver bad news. It is a huge problem to put asbestos right in the UK. They seem to think if you wait long enough the problem will go away. But people are still dying, as asbestos degrades and becomes higher risk.”

Love, loss and activism

Samantha Cox and Joanne Murray lost their fathers to mesothelioma brought on by exposure to asbestos. They now run a support group – called Readley – that assists other patients and their families.

Samantha’s father, Paul Readhead, was a plumber. “When he was an apprentice, he worked with asbestos all the time. That was just the way it was,” she says. He was 62 when he died in January 2015. “I was grieving but by March I felt I needed to do something,” she explains. Samantha met up with Leah Taylor, head of nursing for Mesothelioma UK, and decided to set up a group in her dad’s memory. “And then along came Jo.”

Joanne’s dad, Robin Smedley, was a racing car engineer. “My dad first came to the group in January or February 2016,” Joanne recalls. “His diagnosis was in the summer of 2015 … and there was no hope, no support group [then].” Robin died in 2017 at the age of 75.

Readley now offers financial, legal and bereavement support, as well as therapy, to others in a similar predicament in the northeast of England.

Speaking over tea and cakes at one of their meetings, Samantha remembers her dad. “He was fit and healthy and he died because he worked with asbestos. He was my protector and you know, he died, like other people we know, because he was looking after his family.”

When Joanne’s dad was diagnosed, she says, “It was like a bomb going off for me, personally, it changed everything.” The support group gave her family help at a critical moment. That’s why she now gives back to others, like Helen Bone.

Back at her home, Helen scratches her dog Alfie’s head. “That first month after diagnosis is like a whirlwind,” she says. “I had the world and his wife here, and it only hit me when everything settled down.” She adds, smiling, that she told her brother, “I get up in the morning and I think, yep, still got it, and crack on with my day.”

The median life expectancy for someone living with mesothelioma if treated with chemotherapy alone has until recently not been much more than a year, Professor Dean Fennell, director of the Leicester Mesothelioma Research Programme, explains.

But, he adds, “Things have changed dramatically. We have evidence now of huge movement, in terms of what we can offer patients.” Immunotherapy is making inroads, and an increasing number of clinical trials, including one run by his team that Helen is on, called the MiST trial, using targeted cancer drugs, offer real hope.

But, in the meantime, people are still being diagnosed with cancer from an avoidable risk, says Liz Darlison. “We have known about the dangers of it for nearly 70 years and those who can effect change aren’t doing enough. Another person walks into [the] clinic, and I keep thinking, why do we keep exposing people to this?”

Helen is realistic about her prognosis, but for now, she is relishing life at home, celebrations and everyday milestones. “I’m really open to talk about death, and I’ve talked about it to Mark and with the kids …. You can’t make light of some things, it is just really, really sad,” she says, before adding, with a smile, “I’ll enjoy my day. I want to do nice things and make every year count.”