If a politician’s international relevance is measured by the scale of the global reaction to his or her resignation from high office, then the first minister of Scotland can claim to be one of the most significant world leaders of recent decades.

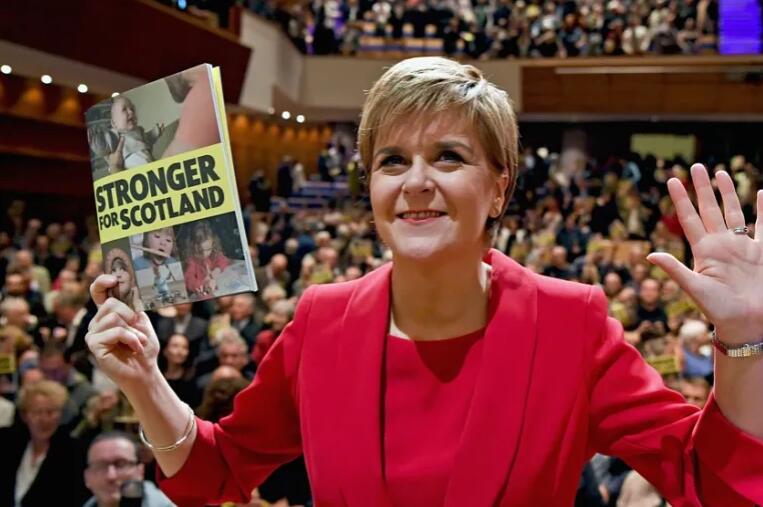

Following Nicola Sturgeon’s announcement last week that she would be stepping down from her role as Scotland’s head of government and leader of the Scottish National Party (SNP), international reactions came thick and fast.

Ireland’s Prime Minister Leo Varadkar paid tribute to Sturgeon as a “true European” following her decision to quit the political limelight after more than eight years as Scotland’s premier.

Former US President Donald Trump, who owns two golf courses in Scotland, also weighed in – albeit less glowingly – bidding “good riddance to failed woke extremist Nicola Sturgeon of Scotland”.

Like Jacinda Ardern, who resigned as New Zealand’s prime minister last month citing political burnout, Sturgeon admitted that the demands of public office had taken their toll. But Sturgeon’s global newsworthiness is especially remarkable considering her role as the political head of a stateless nation – and not a nation-state.

While Scotland, the second-largest nation in the United Kingdom, was granted devolution in the late 1990s in the form of a Scottish Parliament in Edinburgh, sovereignty has remained at London’s Westminster – the political seat of the British state.

But the ties that have bound Scotland to England since the 1707 Act of Union have frayed in recent years.

The political rise of the pro-independence SNP from its maiden electoral victory at the 2007 Scottish Parliament elections led to a referendum on Scottish independence seven years later. Scotland’s electorate might have voted against going it alone by 55 percent to 45 percent, but for the first time in more than 300 years, Scottish independence was legitimised.

Sturgeon assumed the role of Scotland’s first minister in 2014 following the resignation of her longtime friend and mentor Alex Salmond in the wake of the referendum.

Her ongoing commitment to the cause of Scottish statehood, and her own government’s legislative programme, such as tackling Scotland’s alcohol consumption by introducing a world-leading minimum pricing strategy, won her international recognition.

In 2016, she made the Forbes list of the world’s most powerful women.

But just as Scottish independence remains a polarising issue for Scots, so too was the domestic reaction to her shock resignation.

“It was a long overdue resignation,” said Iain McGill, a Conservative Party-supporting businessman and pro-unionist campaigner from Edinburgh, to Al Jazeera. “A big part of her legacy is a divided and entrenched country.”

Today, the SNP is preparing for a life without Sturgeon, who has said she will stay on as party chief and first minister until a new leader is chosen, on March 27.

Among those who have announced their candidacy to replace her are Scottish health secretary Humza Yousaf and finance secretary Kate Forbes, both of whom are less than 40 years of age.

Though Forbes’s campaign for leader has already hit stormy waters after the devout Christian said Scotland’s same-sex marriage laws conflicted with her faith, yet, whoever prevails, will from an electoral perspective have big shoes to fill.

Indeed, Sturgeon was an election-winning machine. The left-of-centre politician led the SNP to Scotland-wide victories at every UK general election during her tenure, a feat she repeated at every Scottish Parliament election.

She campaigned hard against Brexit during Britain’s 2016 in/out European Union referendum – and repeatedly shone a light on Scotland’s electoral decision to remain in the EU, despite majority leave votes from England and Wales propelling the UK out of the bloc. Her pro-EU credentials and support for Scotland’s migrant community won her many admirers.

Scottish Green Party and pro-independence activist Laura Moodie told Al Jazeera: “As a woman in politics, her tenure, while she was subject to very ugly misogyny at times, has created a path for others to follow of a different, more empathetic and personable approach to leadership.”

But, over the last several years, she cut an often-beleaguered figure.

A very public falling out with Alex Salmond after the former first minister was accused of attempted rape and sexual assault (of which he was cleared in court in early 2020) caused her great anguish.

Her attempts to hold another independence referendum were repeatedly thwarted by London, and when the UK Supreme Court last year ruled that the constitution was not within the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament, Sturgeon’s options for a second plebiscite narrowed.

The UK government’s decision last month to block the Scottish Parliament’s Gender Recognition Bill, which would have paved the way for trans-people in Scotland to more easily change their legally recognised gender, weakened her authority further still.

Sturgeon’s ability to inspire devotion and animosity in almost equal measure means that her departure will usher in a new era of Scottish politics.

James Mitchell, a professor at the University of Edinburgh’s School of Social and Political Science, told Al Jazeera: “Sturgeon’s successor will need to focus more on governing devolved Scotland, and addressing issues Sturgeon talked a lot about but failed to get to grips with.”But with both Forbes and Yousaf putting the independence question at the forefront of their respective leadership campaigns, the debate surrounding Scotland’s constitutional future will likely endure.